It might have been Pratts (most excellent name for a life drawing group ever) in Twickenham where I saw Lucy first, if not The Mall Galleries, as we posed from opposite ends of the hall. I saw her before I spoke with her. Across the room, the largest model I’d ever seen, by far. A completely different animal to me, sprawling majestically along the bench. She was quite loud too; I could hear her negotiating her pose with the artists, or explaining it. And she laughed, she was jolly. I could tell she meant business and had plans for me, but I wasn’t sure if I wanted to be involved so I didn’t come forth at first. She was approaching with a notebook and pen and I sensed that she wanted my contact details and to do something awkward like connect! Although I was about 30 I was still pretty shy socially in certain settings, my work place included. I could give it all in the poses, but I didn’t need to make friends yet… We were surely very different and I was trying to write a play.

As I spelt out my email address to her she was adding it to a list. There were quite a few already on the scrap of paper which was nestled in her pad. Where did she find them and how long had she been collecting them? What was she going to do with it? It might have been a few months later I received her newsletter. It was long and rambling and I think she’d suffered from a lengthy uncomfortable pose with a dubious organiser. She wanted to share her experience with us, random models who probably didn’t know each other. She was gathering us in person too, only I couldn’t make it. These emails would appear and she would offer up tutors’ contact details, though I don’t remember following any of them up. I was already well booked, and learnt early that jobs which approached me directly tended to work out better for me than when I wrote to them.

Over time however, the value of this list resource became apparent to all of us. If one became ill, or needed to attend a rehearsal, a quick email could solve one’s inability to fulfil a commitment personally. You could tailor it – ‘slim dynamic female model needed to cover me!’ Luckily for me this category is well catered for amongst life models, and I came to know who was best suited. The trick was finding someone who the artists wouldn’t prefer… as that was something the list couldn’t legislate for. Not only have you let the group down, but also the stand-in is better! That probably happened to all of us at some stage, as well as conversely being the favoured stand-in. Equally important was that the stand-in was reliable and didn’t upset the group (unless you didn’t really like them of course). So the list had to be quality controlled. Tricky situations included being ill and the only available model is nothing like you. They go along to the job, and they receive a comment which could be racist. Obviously being white, I hadn’t experienced that from those people (though could imagine it, it’s not totally out of place). It becomes necessary to ditch that group, but the racism isn’t clear-cut enough that you can easily out them publicly. It was a flavour of what other models may more often encounter.

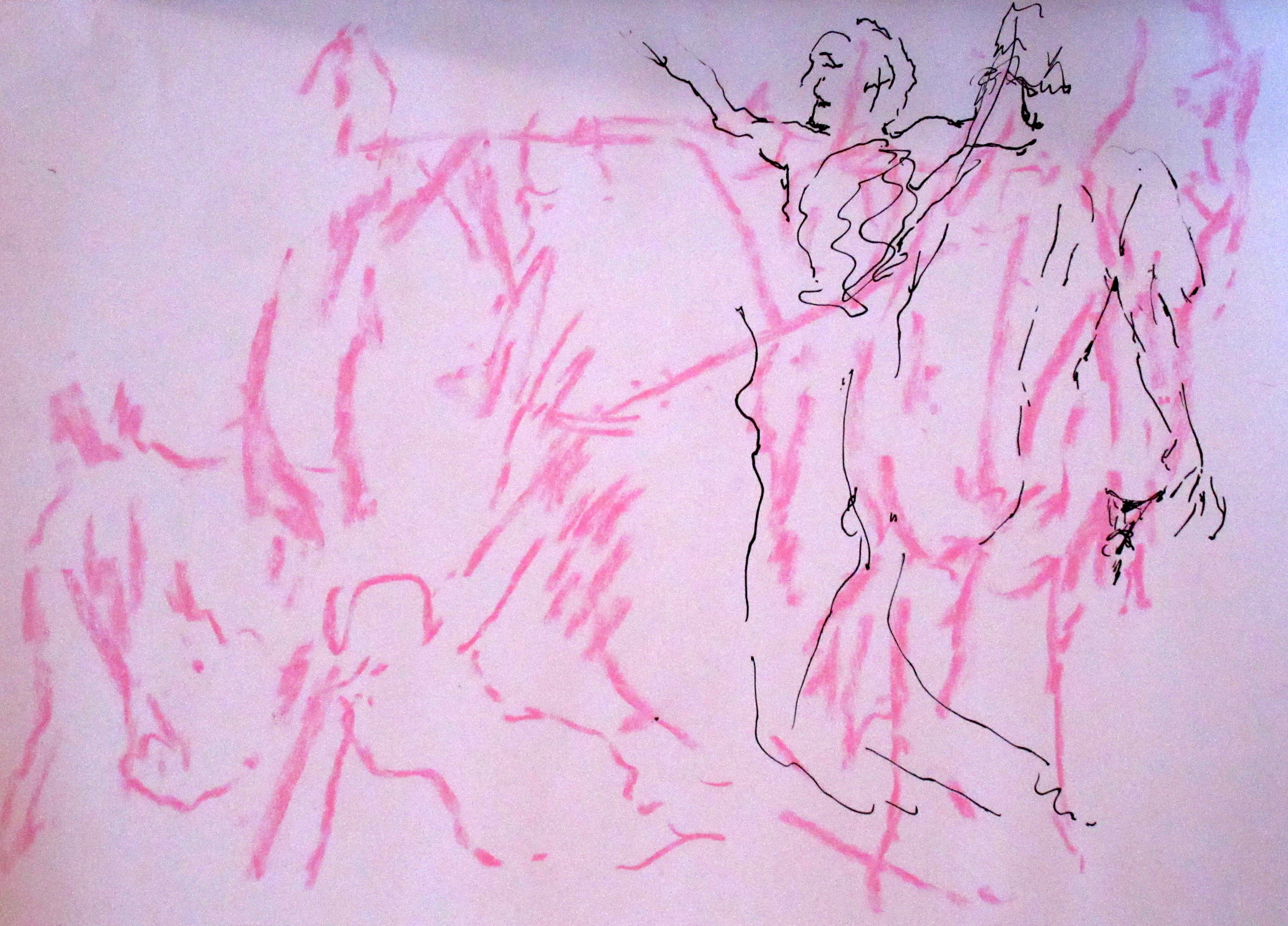

Round the corner from Heatherleys was a tower block estate on the edge of Chelsea. There was a squat inside where Brazilian circus artists and migrants who did not have the right to work in the UK lived. They made excellent models for the ladies who lunch, and Chelsea folk refining their drawing technique. A French male model was supplying drugs to the rest of the models, and one Autumn there was a climax of models breaking down and spinning out. The models were absent, collapsing and in a state of chaos. This energy of disruption was affecting the whole school, and while some students were deeply infatuated with their exotic muses, the uncertainty of the models’ presence pushing their artwork further, it couldn’t go on. Outside of the models’ clique who could tell who was behind it? A change in the system took time to embed in the school, necessitating longstanding models to reapply for the job, submitting various forms and official documents (actually this happened at all the colleges over a number of years). By the end of that process drug sharing was no longer so rampant, and the model pool was less interesting; more limited. Even among those who were legal, the job became less desirable. To maintain the former edge required finding different work, as yet unscathed by an increasingly intrusive bureaucracy.

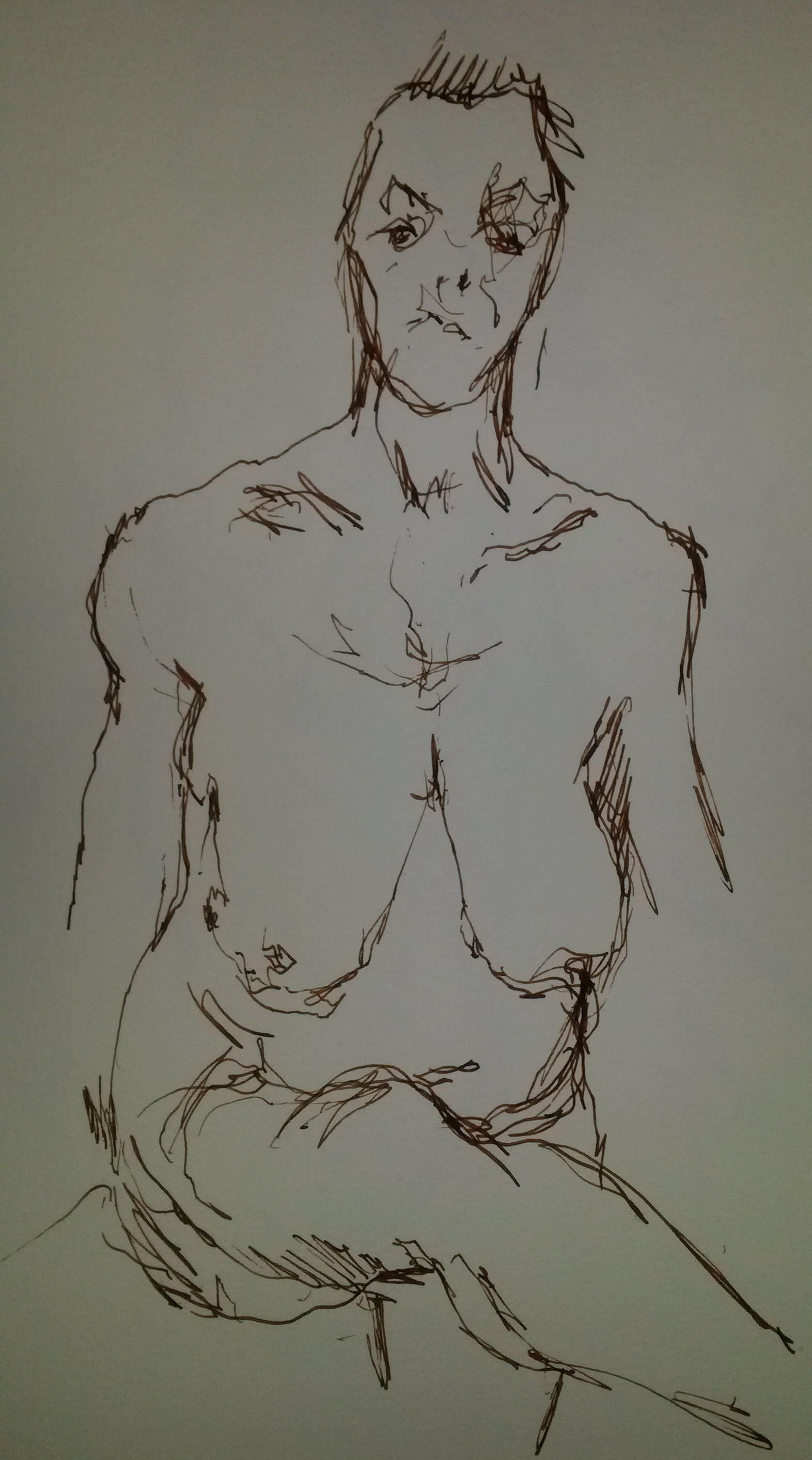

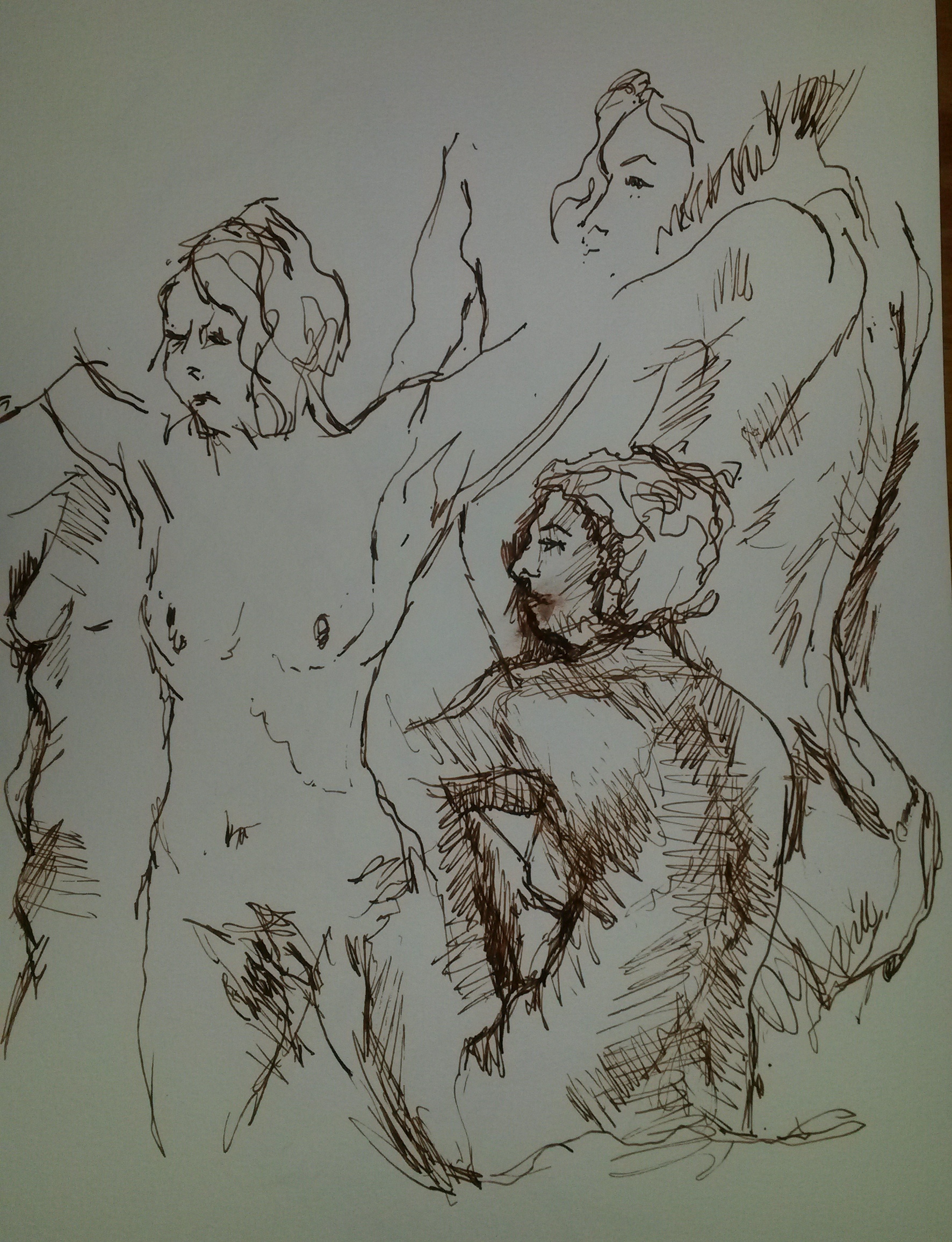

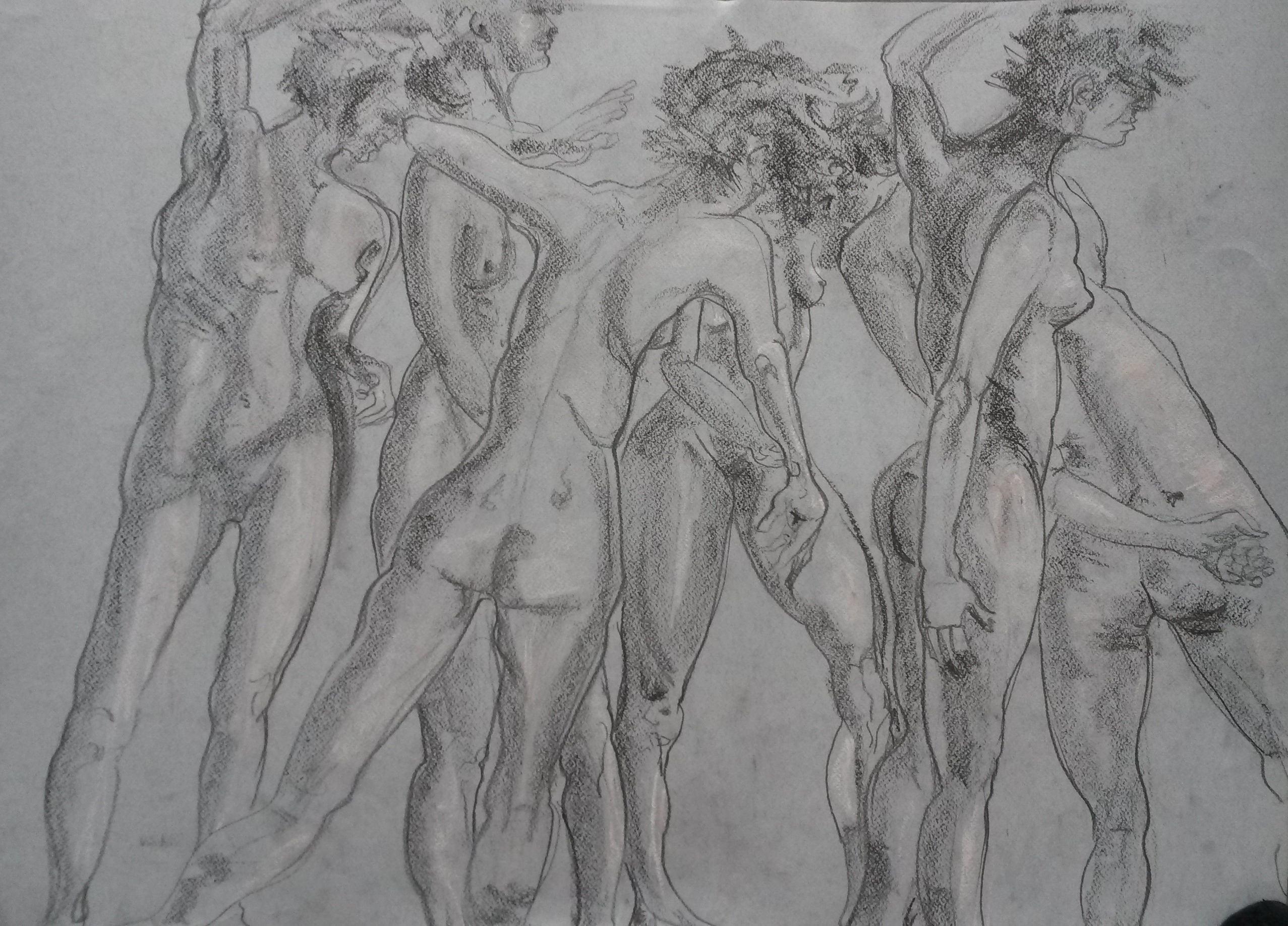

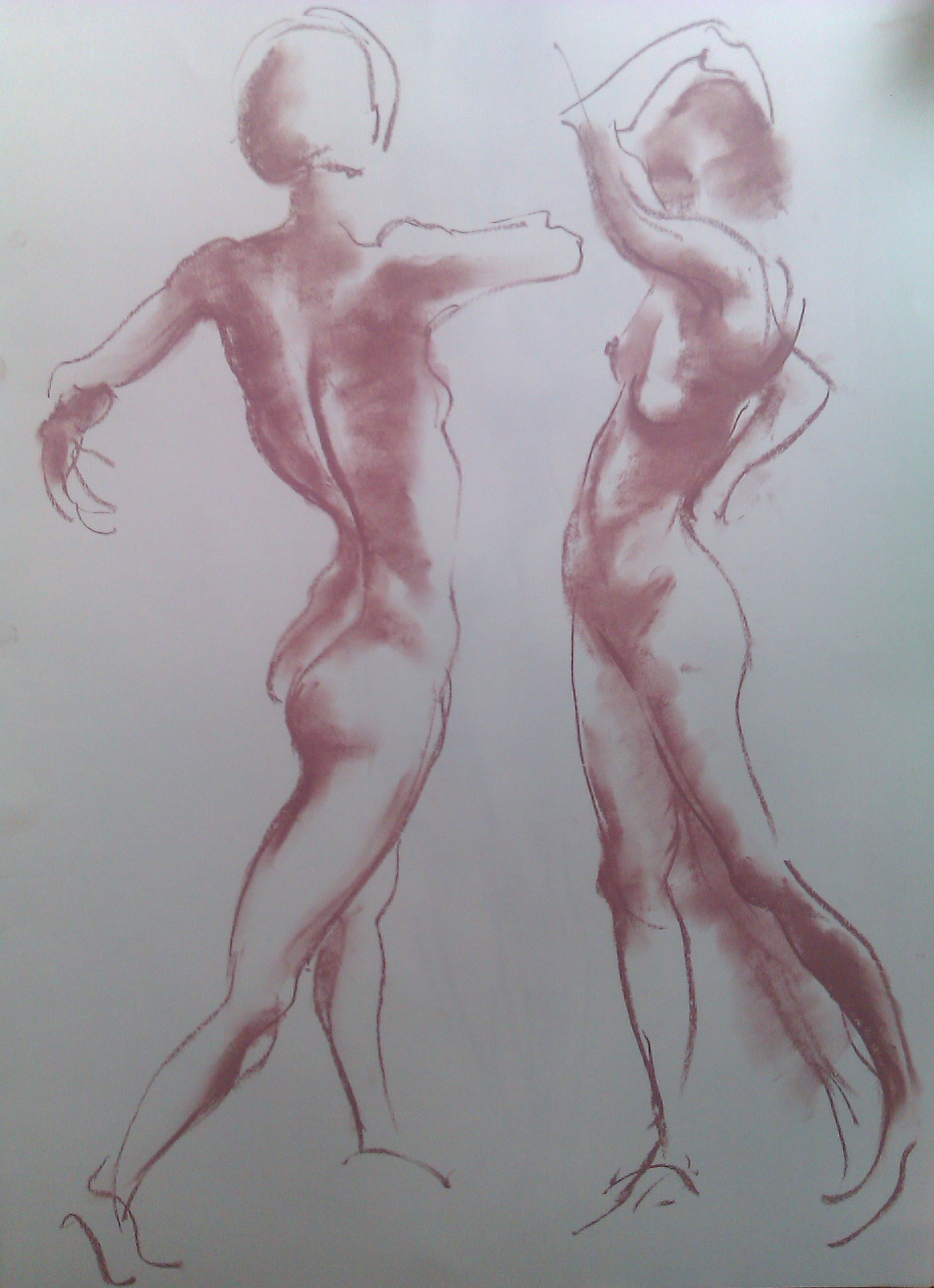

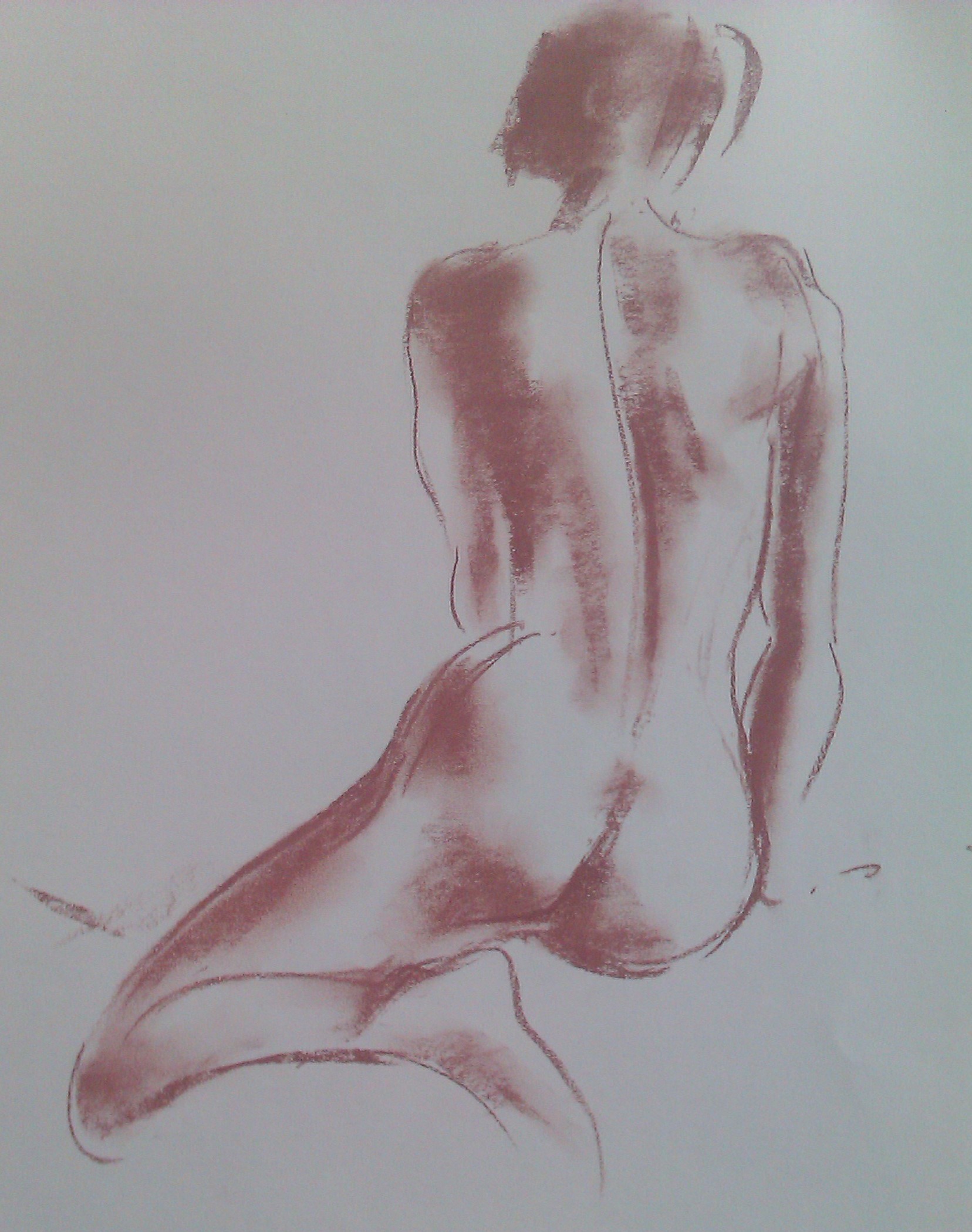

This description of that earlier cohort of models (predating ‘The List’ in fact) highlights how applying excessive red tape to art schools and departments affected life on the ground. I was around just early enough to experience the different species we used to be. When we were edgier and less acceptable, we came from underground, on the fringes of society. We were unafraid to be strange, in fact committed to it. We were exiles and runaways, freaks who embraced our eccentricity. What became a nice job for people who were already quite comfortable, once nudity wasn’t so demonised, had previously been the domain of the brave and the unusual. Some of the pool hasn’t changed; we’ve always been actors and dancers or artists ourselves. And I am not being negative about the changes; I helped to create them. I think it’s good that more people have the chance to try our profession and explore themselves that way. I like that nudity becomes more acceptable – and we still have a long way to go.

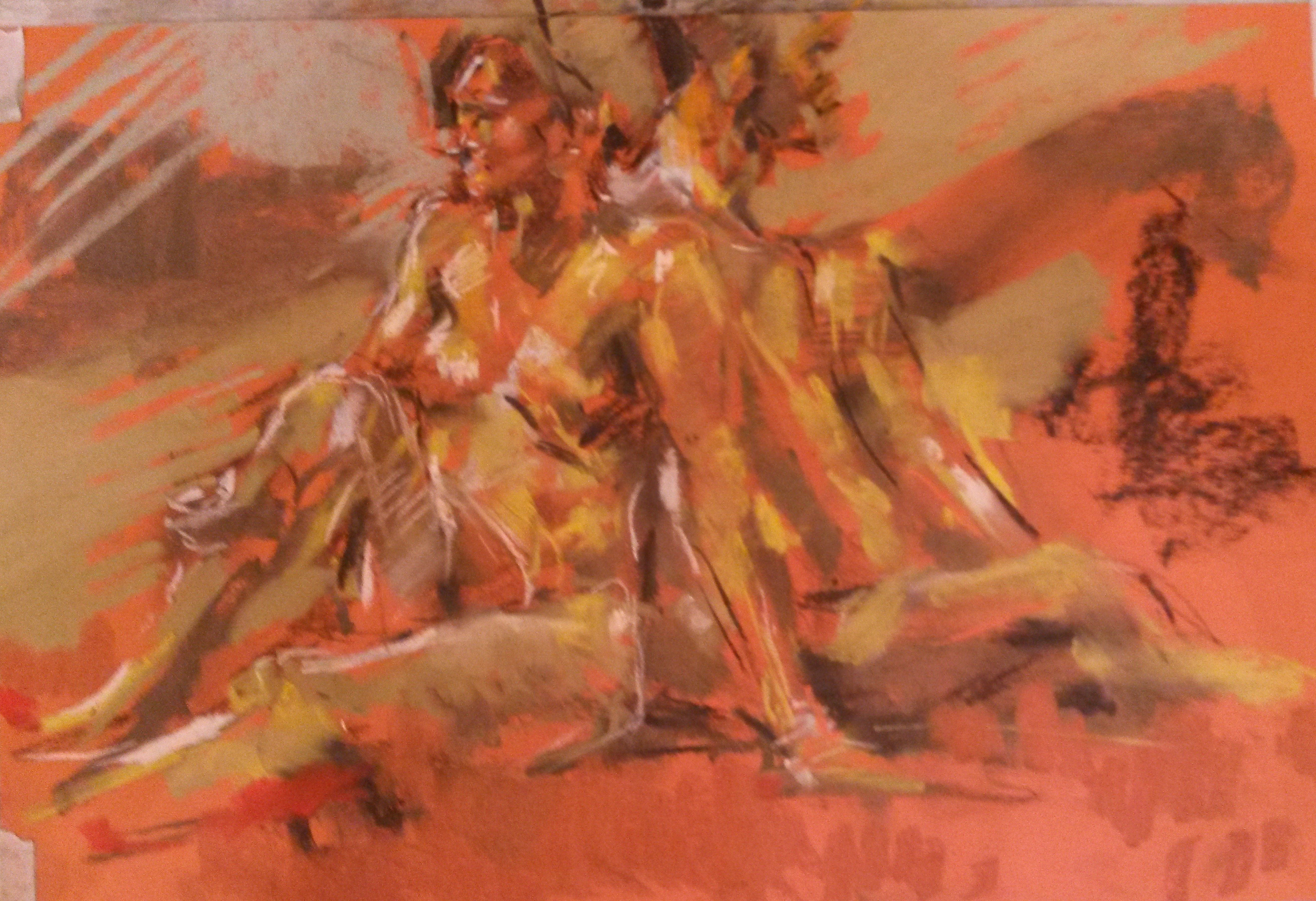

Different currents coexist; while many of us are more comfortable with our bodies, others are swept up in pursuing an eternal youth, fed by late capitalist overdrive, if not sunken in self loathing, very distant from loving their own form. Multicultural inclusivity in fact threatens areas of our liberation, whilst a real fear of perverts escalates the problem. The hope is that we realise part of what makes our land so desirable, is our cultural freedom and openness to accept diversity. We welcome you in all your magnificence, and reciprocity is the only appropriate response. Of course I’m not speaking of the cruder elements encroaching – the far right becoming popular. However naïve I have faith in the light and will always follow it. The news does not have an interest in how many of us are waking up to love ourselves more, and it is this powerful drive which may turn the tide on the negative influences still besetting us.

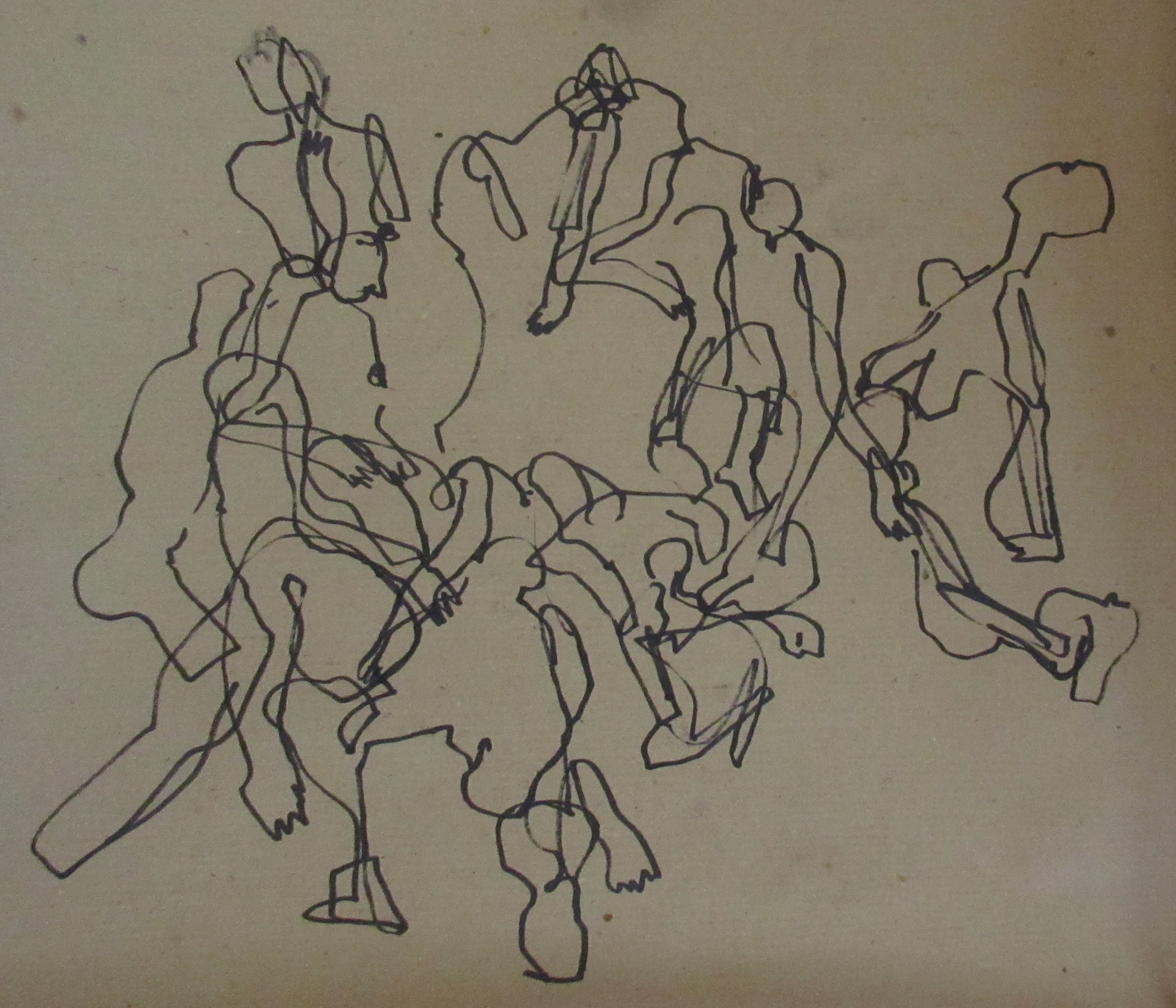

Regardless of the bureaucratic shift, our culture permits personal exploration and individuation. This is really important. I don’t fully know why, but in some other countries it seems people are less willing to stand out and evolve themselves. Perhaps their laws and systems reflect this, but it’s also part of their national psyche. The possibility of pursuing art in later life, whether you initially trained in it when you were young or not, is so vital for growth. Freeing ourselves from the idea that only people who are naturally gifted may create art, is also key. Letting go of judging ourselves too harshly comes into it, and actually pervades an awful amount of our lives. Being open to making a mess and having fun is vital, whether through an artform, cooking, or walking in the woods. Leaving behind the straitjacket of social convention needs to happen if we are to expand into our greatest version of ourselves. Extricating ourselves from herd mentality and instead being ready to follow our individual callings is where the magic happens. To know what that calling is you oftentimes have to slow and quiet down, listen inwards. That voice is there but you must give it the right conditions.

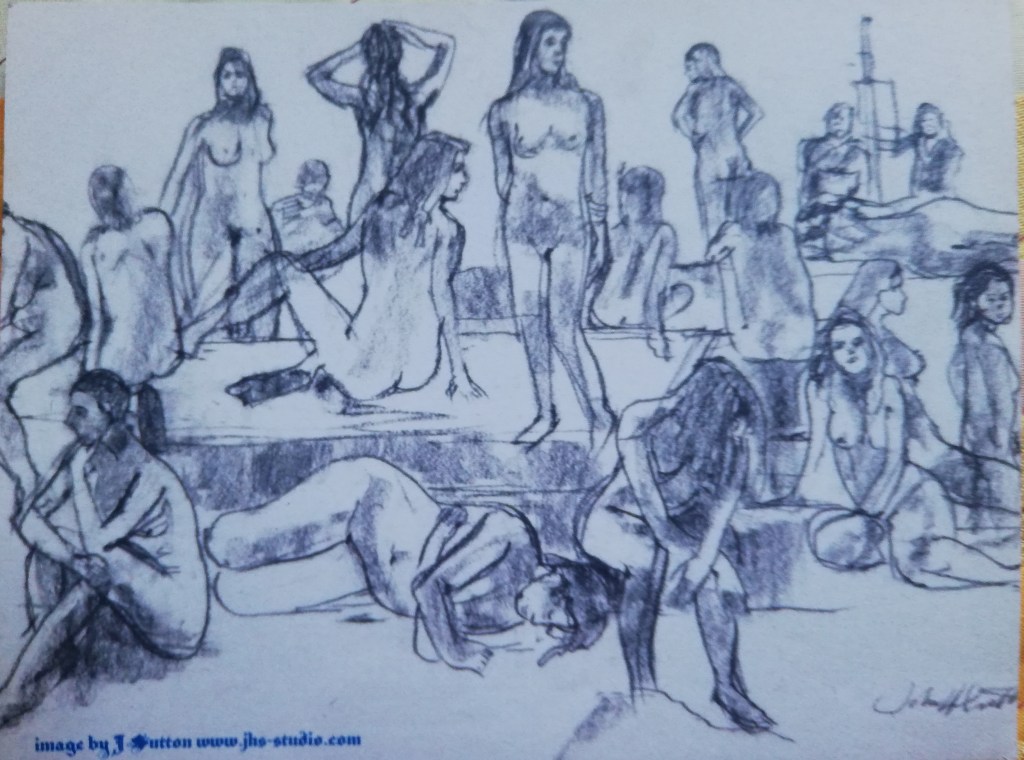

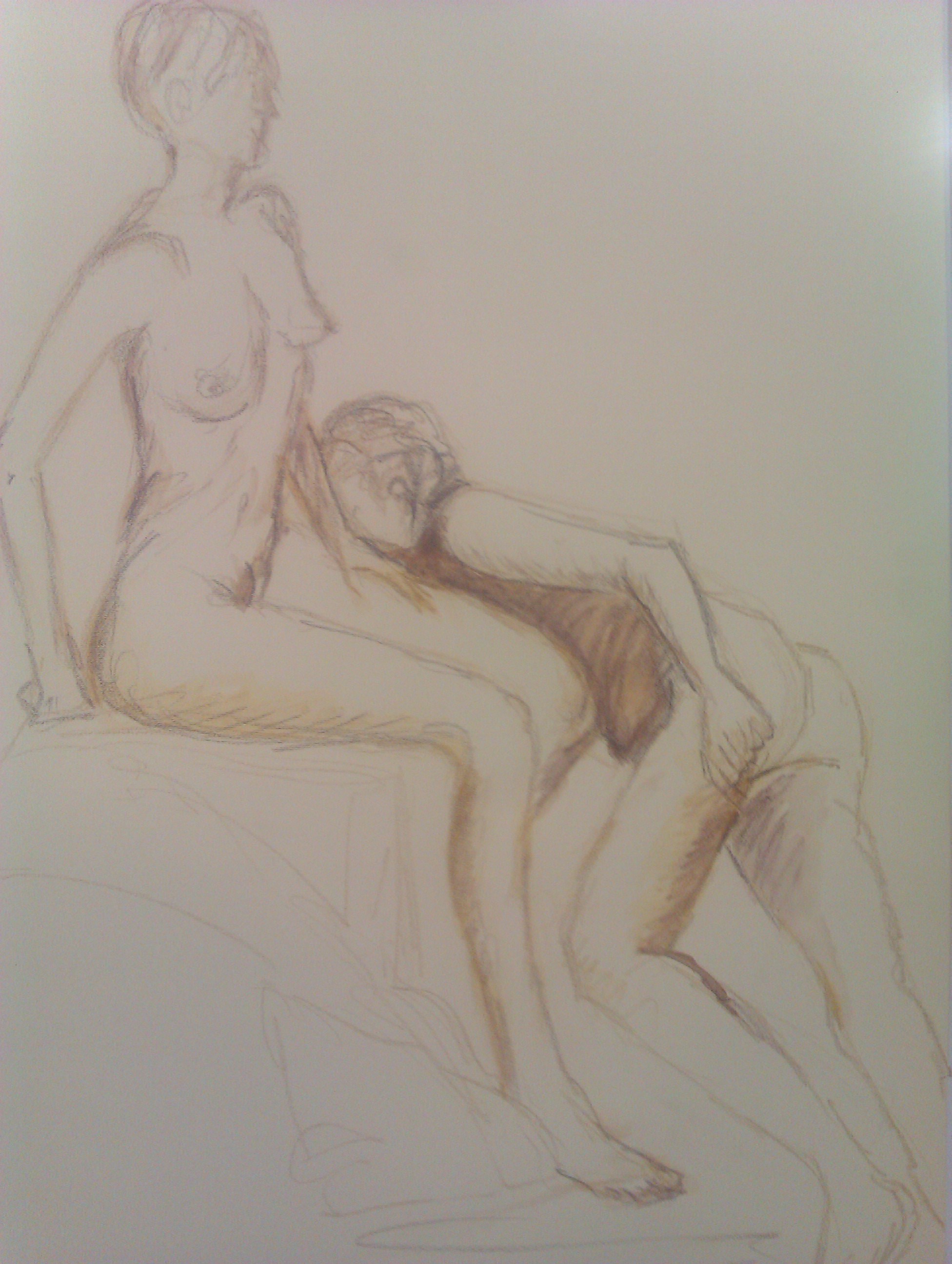

Long before the rise of fashionable life drawing in recent years, there were ever groups of older (and sometimes not so old!) people round the UK meeting up to draw nudes. On a Tuesday morning in suburbia, or a Wednesday afternoon in the home counties; wherever it is be it church hall or community centre, someone’s garage or above a pub… this has been going on for decades! It crosses the class system I was delighted to find. Working class artists are at it just as much, even if fewer of them may afford the likes of Heatherleys or other traditional art schools. In these groups, the social aspect is valuable too. It’s about community and what makes life worth living. Older members die off and new ones must be recruited, so the group is open to those who haven’t done art before but would like to try now. Not always, but I do see that.

The models have always been very international, it’s part of our pedigree and makes us more interesting. We bring more relaxed attitudes, or escape authoritarian ones. We feel freer to express ourselves on foreign soil, away from family judgement. Being secular is what makes British life so available. Over the years I have been friends with several models, British and from elsewhere. Sometimes an assumption pervades that being born British life must be easier for one, but I don’t think it’s so simple. Often those who make it here from elsewhere are strong to have made that move. Whether they escaped, or chose a culturally advantageous location, there is strength in upping roots to make a new life in another country. Many people can’t, and I know I was limited in my earlier years by such predicaments. From addiction to being caught in abusive relationships, these circumstances hold one back, wherever you are.

Being a model can be a leveller, a means by which a new arrival to the UK may obtain work easily, without knowing much of the language, and purely by the magnetism of their character, ability to turn up on time and hold still, play on a reasonably level playing field with their British sisters and brothers. Most of my model colleagues have been foreign, and from the EU, which has not become distant as was feared, since Brexit. Many pass through modelling on the way to something better paid and more specialised, as well as Motherhood. More arrive and emerge. We are constantly renewing!

This series of posts about my life modelling journey is also featured on the Newington Green Life Drawing group’s site.